Dilemma of the “Friendship-with-No-Limit:” Understanding the People’s Republic of China: Ambiguity in the Russo-Ukrainian War

Russia’s widely condemned invasion of Ukraine has put the People’s Republic of China in a foreign policy quagmire. The PRC has adopted a series of ambivalent and contradictory responses to the crisis. It offered political support to Russia by abstaining on the UN resolution condemning its invasion of Ukraine1 and criticizing Western sanctions and military aid to Ukraine.2 However, the Chinese ambassador walked back on the February joint statement that proclaimed a “no-limit” friendship by recognizing “the United Nations Charter and basic norms of international law” as the bottom line.3 Although the Chinese government tried to portray itself as neutral and constructive internationally, translated domestic media content that parroted Russian propaganda ran counter to this image. Despite political support, the PRC has given no military aid to Russia and has been reluctant on economic support due to fear of secondary sanctions. For example, the Asian Investment and Infrastructure Bank (AIIB), in which the PRC holds 24.41% of voting power, ceased its activities in Russia and Belarus.4 The PRC’s seemingly pro-Russia stance has attracted criticism, but there is still hope of it playing a mediating role.5 defensive realist and constructivist logic best explain the PRC’s ambiguous response. The invasion has not affected the PRC’s core security interest. Instead, it has tarnished the PRC’s reputation, thus obstructing its quest to be an international norm-setter. Contrary to the intuitive predictions of increasing Sino-Russian codependency, the war is likely to cause setbacks and uncertainty in their cooperation.

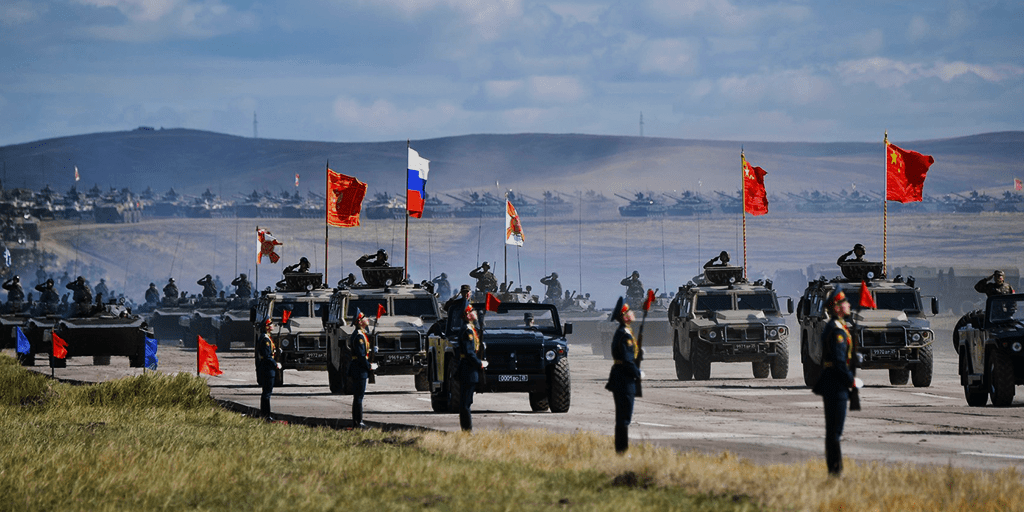

The PRC and Russia have been on the course for deepening political, military, and economic partnerships since the 1990s. This has manifested in increased military collaboration, including frequent high-level security consultations (for example, Shanghai Cooperation Organization), joint military exercises, and partial interoperability.6 The PRC has also strengthened its economic ties with Russia through One Belt One Road (OBOR) and energy deals, even in the wake of the 2014 Ukraine crisis and western sanctions.7 Debates on the nature and driving forces of such a relationship would shed light on its sustainability through the current crisis. Korolev, Senior Lecturer at the University of New South Wales, argues that shared interest at the systems-level — balancing against US and Western hegemony. The shared system-level interest takes precedence over their intense regional competition.8 Owen, Professor of Politics at the University of Virginia, similarly predicted closer Sino-Russian cooperation because the authoritarian leaders in both countries fear isolation by Western-aligned neighbours and Western-inspired democratization.9 Moore, a political scientist specialized in Chinese politics, is less optimistic about the strength of such a relationship. He argued that both countries prioritize immediate interests instead of anti-US alignment due to distrust and hyper-utilitarian approaches. Instead of viewing the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and OBOR initiative as signs of close partnership, he pointed out the two countries’ divergent interests and mistrust of each other’s intentions in Central Asia and the Far East.10

Domestic institutions and actors also contribute to the PRC’s current stance on the war. Deng Xiaoping set a pragmatic, low-profile, and economic-focused tone for PRC foreign policy, deviating from Mao’s revolutionary and often interventionist outlook. The Jiang and Hu administrations adhered to Deng’s principles to some extent but gradually increased the PRC’s international presence and assertiveness. Xi Jinping, who adopted the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation as his administration’s mandate, accentuated the PRC’s existing inclination toward “great power diplomacy” and further centralized decision-making power in his own hands. Besides being more confrontational about security issues, Xi sought to transform the PRC from an international norm taker to a norm setter. This ambition manifested in the China Dream ideology, a nebulous concept that sought restoration of China’s great power status and institutional building, such as the Belt and Road Initiative and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.11 Foreign policy decision-making power rests with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership, specifically the Politburo Standing Committee, instead of the government. Relevant ministries, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Commerce, would advise the committee and implement its decisions. Although it is conventional for the Chairmen of the PRC to take a dominant role in foreign policy, Xi has gone further by creating and chairing new leadership small groups (LSG) on security and cyberspace. He has also upgraded LSGs in foreign affairs, finance, and economics, deepening reform and cybersecurity into formal commissions. Now, there are even fewer officials than before who play a decisive role in Chinese foreign policy.12 There are more non-traditional actors, such as think tanks, businesses, and local governments, that participate in foreign policy, but decision-making in high-profile crises (like the Russo-Ukrainian War) is concentrated among Xi and a select few Politburo members.

The Russo-Ukrainian War has elucidated China’s priority: maintaining the beneficial status quo instead of challenging American hegemony. China’s cautious reaction, falling short of supporting the Russian invasion, is a manifestation of its longstanding defensive instead of offensive realist thinking. The realist school posits that states pursue rational self-interest (security) in an anarchical international environment. Offensive realists understand security as zero-sum and conflicts as irreconcilable. On the contrary, defensive realism argues that intentionally undermining the security of others is unnecessary for states to be secure themselves. International anarchy punishes instead of rewards aggression since aggression provokes other states to cooperate and target the aggressor. China switched from offensive realism to defensive realism after the Deng Administration. Recognizing security dilemmas, accepting external constraints by joining international organizations, and institutionalizing cooperation with neighbours are all hallmarks of defensive realism.13 Moreover, since the Deng Administration, China has shown no attempts to replace the US as a global hegemon or establish an alternative international system, a prescription of offensive realists.14 The US and many of China’s neighbours perceived Xi’s more aggressive response to regional issues as a departure from the entrenched defensive realist thinking. They reacted accordingly by phasing out engagement for containment. Offensive realism predicts power-maximizing behaviour that seeks to topple the current hegemon through balancing. If China operated under offensive realist logic, it would actively assist Russia politically, economically, and militarily. Despite parroting Russian propaganda, China has chosen to provide limited political support, as demonstrated in casting an abstention vote on UN condemnation of the invasion; minimum economic assistance, as demonstrated by increasing energy imports but no attempt to help Russia circumvent sanctions; and most importantly, no military support. In sum, “friendship with no limit” with China yielded Russia very little benefit compared to western aid to Ukraine. China also sought to legitimize its neutrality by citing international norms. For example, Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Hua Chunying justified China’s stance and proposal for peace by citing the Charter of the United Nations, that “nations ought to follow its principles to resolve conflicts peacefully.”15 When confronted about complicity in the invasion, PRC’s Ambassador to the US, Qin Gang assured the international community again by acknowledging the Charter as the baseline for Sino-Russian relations.16 This behaviour counts as “exercis[ing] self-restraint and willing to be constrained by other countries,”17 a sign of a country following a defensive realist strategy.

China’s relatively cautious response to Russia’s call for assistance reflects some mismatch between Russian and Chinese interests. There was no direct incentive for China to be involved in the conflict on behalf of either side because Ukraine was outside China’s core security concerns and only tangentially relevant to military modernization. The latest national defence white paper, “China’s National Defense in the New Era (2019),” emphasizes challenges in the Asia Pacific region, such as Taiwan’s pursuit of independence, American and allied presence, and disputes over Uotsuri Jima/Diaoyu Dao. It also gives priority to military modernization, border security, and anti-terrorism.18 Moreover, economic links with Ukraine are not crucial for China because bilateral trade is only valued at 15.4 billion USD (2021), and Ukraine did not participate in the main Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) project.19 China’s reliance on Ukrainian arms exports could be a rift in its alignment with Russia since it gives the PRC access to Soviet technology that Russia has preferred to keep confidential.

However, many contemporary reports overstate the importance of Ukrainian weaponry in China’s decision-making. The country is more willing than Russia to offer cutting-edge technologies, such as missile and aerospace technology to China. Russia briefly ceased a co-production agreement with China because the latter reverse-engineered and duplicated the Su27 aircraft. In contrast, Ukraine did not negatively react to China duplicating the Su33 it sold.20 However, Russia’s dominance over China’s weapon import sector (accounting for 77% of total weapon import value) overshadowed Ukraine’s 6.3% share.21 The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute observed that the PRC’s dependence on Ukrainian technology was already in decline since the early 2000s as indigenous research and development in China was catching up. Moreover, intense American backing against the invasion would incentivize Ukraine to halt sensitive technology transfers to China.22 Deepening Sino-Russian military cooperation after the 2014 Annexation of Crimea further diminished Ukraine’s importance, as Russia switched from “defense-equipment-for-cash” to interlocking military equipment development and production.23 These collaborations made the previously coveted aerospace technology more accessible to China. However, there were no signs of these ties being used as leverage to entice China into the war in Ukraine since China was an equal partner with some advantages and was extremely cautious not to provoke any US sanctions.

Although the invasion had few direct impacts on China’s security, it dealt a negative blow to China’s aspiration to be a “responsible great power” and global norm setter. China was in an uneasy position in the post-Cold War international system. It rose as a great power within the US-dominated liberal international system, but the system was not built with its input. Recognizing such conditions, Chinese policymakers and scholars agreed on more proactive participation on the international stage. They saw the benefit of acting as the tacit manager in maintaining the stability of this largely Western-designed system by providing global public goods.24 Such leadership positions in the existing system were viewed as opportunities to reshape disadvantageous norms and principles in the long run.25

China’s tacit support to Russian aggression in the war set back progress in elevating China’s normative power. First, refusing to condemn Russia’s invasion jeopardized China’s consistent effort to portray itself as a champion of the principle of sovereignty, non-interference, and territorial integrity. This position was first stated in the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence (territorial integrity and sovereignty, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence) during the Bandung Conference. The Deng administration adopted it into the 1982 Constitution and replaced Maoist intervention with the principles of reintegration into the international community.26 The fundamentalist interpretation of sovereignty serves as an alternative and challenge to the concept of sovereignty as responsibility. The latter warrants intervention when states fail at their responsibility to uphold human rights. China fended off criticism and potential intervention for domestic issues and countered the pressure of third-wave democratization by appealing to respect for sovereignty stipulated by the UN Charter. It also justified maintaining cooperation with countries sanctioned for human rights abuses and rallied like-minded nations who face similar concerns. Most importantly, China routinely legitimized its claim over disputed territories and Taiwan by categorizing them as internal affairs.27 Refusal to condemn Russia’s actions runs counter to these long-held principles, thus shaking the credibility of China’s iterations.28 Credibility in upholding national sovereignty matters highly to developing countries with which China seeks to collaborate more closely. Developing countries have reason to doubt China’s commitment to sovereignty since China pledged to “protect the unity and territorial integrity of Ukraine” in 2013 and “provide corresponding security assurances to Ukraine in the event of aggression or threat of aggression against Ukraine using nuclear weapons” in 1994.29 However, condemning Russia could also be problematic since it would lend credence to the American presence in the Asia-Pacific. China sympathized with Russian concerns about NATO expansion in Eastern Europe and repeatedly condemned a so-called “Cold War mentality.”30 It shared the same weariness regarding the potential of an Asian NATO, taking the shape of AUKUS and The Quad.31 Thus, there is little room for China to refute Russia’s rationale without compromising its stance against the US’s growing alliances in Asia.

Second, the war disrupted one of China’s most ambitious projects to participate in international norm-making: the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Distancing itself from the conflict to protect the already slow progress of BRI is an essential factor in China’s foreign policy considerations. The northern route of the China-Europe Railway Express (CRE), crucial to BRI logistics, runs through Russia to reach the German city of Duisburg. 32Many major companies, such as BMW, Audi, Maersk, and DHL, avoided CRE because of the EU and American sanctions on the Russian railway. Current sanctions do not directly prohibit companies from using railway transiting through Russia and Belarus so long as the goods are not originated or delivered to the two countries. However, complications of freight settlement, the uncertainty of future sanctions, and the potential seizure of goods have compelled corporations to avoid this route.33 Coupled with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, total trips through CRE during the first half of 2022 increased by only 2 percent compared to the same period in 2021. This represented a significant setback as “neither of the yearly growth rates had dipped below 20 percent in previous years.”.34 As mentioned above, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) , an important funding source for BRI projects, paused its loans to Russia and Belarus after the invasion to avoid sanctions. Moreover, the PRC’s Russia apologist attitude has tarnished its image and BRI projects in Central and Eastern European countries, in addition to the mask diplomacy and Uyghur genocide controversy.

The Russo-Ukrainian war marks a tectonic shift in geopolitics, creating a shockwave of change and uncertainty. Some predict that economic codependency and a shared sense of hostility against the liberal international order will inevitably push China and Russia closer together. China’s ambivalent response has highlighted some incompatibility in this otherwise growing partnership. Would it accelerate or disrupt the trend of increasingly tightening Sino-Russian partnerships? Russian leaders have repeatedly expressed strong interest in a closer relationship with China as their nation becomes increasingly exhausted and isolated. In this scenario, China would have more power to decide the direction of their partnership depending on Russia’s strategic value. This paper argues that it was not in the PRC’s interest to be perceived as pro-Russia internationally because such perception has been damaging to China’s credibility and prospect of becoming an international rule-setter. Since China has been prioritizing immediate regional security instead of the pursuit of global hegemony, the cost of an alliance with Russia outweighs the benefit. These drawbacks contributed to China’s fragile neutrality but do not necessarily foretell a cooling down or deterioration of the Sino-Russian relationship. These independent variables are likely to affect the post-war, long-term Sino-Russian relationship, thus worthwhile for future research: Russia’s post-war capacity, US-led containment strategy, compatibility of the two countries’ security outlook (defensive or offensive realism), and progression of global integration. These factors affect whether China views Russia as a liability or an asset. If China maintains its defensive realist strategy and integrationist approach, Russia’s aggressive behaviour would be detrimental to China’s normative and economic interest while less constructive to its security aims. However, as China’s economic and political integration with the rest of the world becomes challenged, the tension in the Asia-Pacific region rises, and Russia weakens during the war, the future of this partnership of convenience remains less indisputable than fiery rhetoric shows.

- Mark Magnier, “Ukraine War: China Does Not Support UN Vote Blaming Russia for Humanitarian Crisis,” South China Morning Post, March 25, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/3171778/ukraine-war-china-does-not-support-un-vote-blaming-russia-humanitarian. ↩︎

- Guy Faulconbridge, “China’s Xi Criticises Sanctions ‘Abuse’, Putin Scolds the West,” Reuters, last edited June 23, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-xi-criticises-sanctions-abuse-putin-scolds-west-2022-06-23/. ↩︎

- “China Envoy Says Xi-Putin Friendship Actually Does Have a Limit,” Bloomberg, March 24, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-24/china-envoy-says-xi-putin-friendship-actually-does-have-a-lmit. ↩︎

- Joseph Torigian, “China’s Balancing Act on Russian Invasion of Ukraine Explained,” The Conversation, March 10, 2022, https://theconversation.com/chinas-balancing-act-on-russian-invasion-of-ukraine-explained-178750. ↩︎

- Yuwen Deng, “客座评论:北京会做俄乌战争的调停人吗?” DW, edited March 14, 2022, https://p.dw.com/p/48R4v. ↩︎

- Alexander Korolev, “Measuring Strategic Cooperation in China-Russia Relations,” in The United States and Contemporary China-Russia Relations, ed. Brandon K. Yoder (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022), 38-43. ↩︎

- Huiyun Feng, “Partnering Up in the New Cold War? Explaining China-Russia Relations in the Post-Cold War Era,” in The United States and Contemporary China-Russia Relations, ed. Brandon K. Yoder (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022), 95-99. ↩︎

- Alexander Korolev, “Systemic Balancing and Regional Hedging: China–Russia Relations,” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 9, no. 4 (2016): https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pow013, 397. ↩︎

- John M. Owen VI, “China and Russia Contra Liberal Hegemony,” in The United States and Contemporary China-Russia Relations, ed. Brandon K. Yoder (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022), 135-140. ↩︎

- Gregory J. Moore, “China, Russia and the United States: Balance of Power or National Narcissism?,” in The United States and Contemporary China-Russia Relations, ed. Brandon K. Yoder (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022), 60-65. ↩︎

- Marc Lanteigne, Chinese Foreign Policy: An Introduction, revised and updated third edition (London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 97-108. ↩︎

- Jean-Pierre Cabestan, “China’s Foreign and Security Policy Institutions and Decision-Making Under Xi Jinping,” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 23, no. 2 (2021): 13-14, https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120974881. ↩︎

- Tang Shiping, “From Offensive to Defensive Realism: A Social Evolutionary Interpretation of China’s Security Strategy,” in China’s Ascent, eds. Robert S. Ross and Zhu Feng (Cornell University Press, 2017), 152-156. ↩︎

- Marc Lanteigne, Chinese Foreign Policy: An Introduction, Third edition (London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016) 97-108. ↩︎

- Dong Xue and Ma Zhuoyan, “外交部发言人就乌克兰问题、美俄关系等答记者问,” Central Government of PRC, last edited February 24, 2022, accessed September 3, 2022, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-02/24/content_5675296.htm. ↩︎

- “China Envoy Says Xi-Putin Friendship Actually Does Have a Limit,” Bloomberg, last edited March 24, 2022, accessed August 28, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-24/china-envoy-says-xi-putin-friendship-actually-does-have-a-limit. ↩︎

- Tang Shiping, “From Offensive to Defensive Realism: A Social Evolutionary Interpretation of China’s Security Strategy,” in China’s Ascent, eds. Robert S. Ross and Zhu Feng (Cornell University Press, 2017), 152. ↩︎

- State Council,“新时代的中国国防,” Central Government of the PRC, last edited July, 24, 2019, accessed September 3, 2022, http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-07/24/content_5414325.htm. ↩︎

- Katherine Gan,“Ukrainian-Chinese Relations in the framework of Belt and Road Initiative: Perspectives, Problems, and Cultures Interactions,” Ukrainian Policymaker 8 (2021), 38, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352124141. ↩︎

- Gregory J. Moore, “China, Russia and the United States: Balance of Power or National Narcissism?,” in The United States and Contemporary China-Russia Relations, ed. Brandon K. Yoder (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022), 64. ↩︎

- Marynne Xue, “China’s Arms Trade: Which Countries Does It Buy From and Sell to?” South China Morning Post, last edited July 4, 2021, accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3139603/how-china-grew-buyer-major-arms-trade-player. ↩︎

- Greg Torode, “Analysis: Ukraine Crisis Threatens China’s Discreet Pipeline in Military Technology,” Reuters, last edited March 3, 2022, last edited September 4, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/ukraine-crisis-threatens-chinas-discreet-pipeline-military-technology-2022-03-03/. ↩︎

- Mercy A. Kuo, “How China Supplies Russia’s Military: Insights from Alexander Korolev,” The Diplomat, last edited May 9, 2022, accessed September 3, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/05/how-china-supplies-russias-military/. ↩︎

- Chris Alden and Daniel Large, “On Becoming a Norms Maker: Chinese Foreign Policy, Norms Evolution and the Challenges of Security in Africa,” The China Quarterly 221 (2015), 127, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741015000028.

↩︎ - Ian Clark, “International Society and China: The Power of Norms and the Norms of Power,” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 7, no. 3 (2014), 318, https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pot014. ↩︎

- Marc Lanteigne, Chinese Foreign Policy: An Introduction, revised and updated third edition (London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 97-108. ↩︎

- “Historical Legacies, Globalization, and Chinese Sovereignty Since 1989,” in Sovereignty in China, vol. 4, ed. Maria A. Carrai (Cambridge University Press, 2019), 175-181. ↩︎

- Li Li, “Current Criticisms and Reframing of the Noninterference Principle of China,” The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis 28, no. 4 (2016), 564-565. ↩︎

- Kawashima Shin, “China and the War in Ukraine: Anatomy of a Tightrope Act,” Nippon, last edited April 26, 2022, accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.nippon.com/en/in-depth/a08101/. ↩︎

- “王毅阐述中方对当前乌克兰问题的五点立场,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, last edited February 26, 2022, accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/wjbzhd/202202/t20220226_10645790.shtml. ↩︎

- “中国担忧北约扩张的原因——亚太版“北约”出现的可能与背景,” BBC, last edited May 19, 2022, accessed September 5, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/world-61470201. ↩︎

- “What Is the China-Europe Railway Express, and How Much Pressure Is It Under from the Ukraine Crisis?” South China Morning Post, last edited March 6, 2022, accessed, September 3, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3169239/what-china-europe-railway-express-and-how-much-pressure-it. ↩︎

- Markus Keuper, “The Implications of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the Future of Sino-European Overland Connectivity,” Austria Institut Fur Europa, last edited June 2022, accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.aies.at/download/2022/AIES-Fokus-2022-06.pdf. ↩︎

- Ji Siqi, “China-Europe Rail Shipping Takes Hit from Ukraine War,” South China Morning Post, last edited July 29, 2022, accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3187070/china-europe-rail-shipping-growth-slows-ukraine-war-pushes. ↩︎