Secrecy, Surveillance, and the Zimmermann Telegram

Ankur Phadke | Originally Published: 17 January 2026

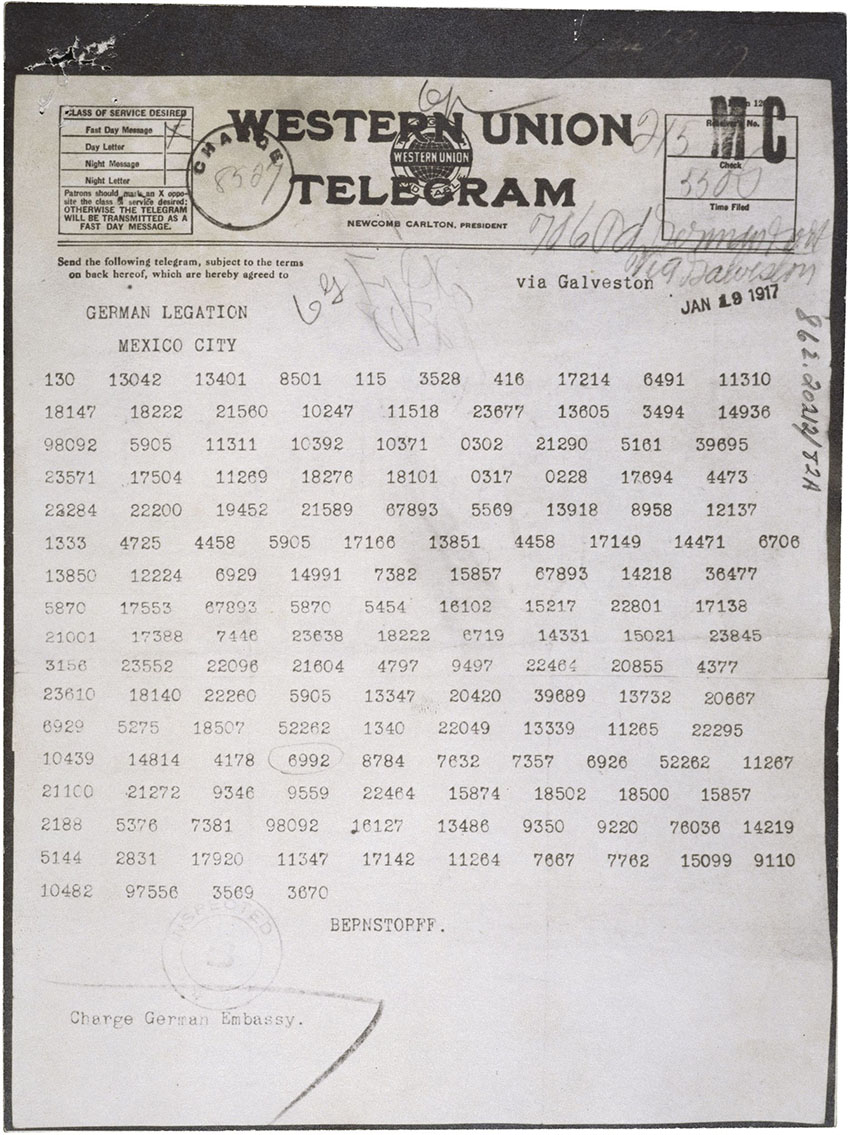

Image courtesy of the National Archives.

Britain’s release of the Zimmerman Telegram to the United States weeks after intercepting it was seen as a calculated move to draw the U.S into the Allies’ war against Germany. Later declassifications and analysis by historians revealed a deeper motivation behind this decision that is rooted in the British Intelligence Services. This article argues that Britain’s delay of informing the United States of the Zimmermann Telegram was not only a diplomatic maneuver to bring it into war, but a protective mechanism to conceal the full capability of British intelligence in intercepting codes through American communication channels. This article will first examine the argument that Britain’s delay in informing the United States of the Zimmermann Telegram was an effort to draw the U.S into an alliance against Germany. It will then explore a deeper aim later uncovered by scholars, which was to protect the secrecy of British codebreaking and surveillance operations in American networks.

To understand why Britain’s delay was initially interpreted as a diplomatic maneuver, it is necessary to consider the state of American–European relations in early 1917. Although the United States maintained formal neutrality during World War I, tensions with Germany had steadily increased due to German submarine warfare targeting merchant shipping. Nonetheless, the Americans supplied the Entente with significant loans and military equipment. However, the British officials believed that American participation was essential to securing victory against Germany, yet President Woodrow Wilson remained committed to non-intervention. As a result, British policymakers were increasingly frustrated by what they viewed as American restraint in the face of repeated provocations. Given this context, the Zimmermann Telegram appeared to offer a potential catalyst for American entry into the war, as it directly implicated U.S. territorial security rather than abstract economic or diplomatic interests.

The Zimmermann Telegram was widely viewed as more politically explosive than previous German actions because it proposed a direct threat to American sovereignty. By encouraging Mexico to ally with Germany and promising the return of lost southwestern territories, the telegram transformed the war from a distant European conflict into an immediate danger at the United States’ southern border. Unlike submarine warfare, which primarily affected commerce and neutral shipping rights, the telegram suggested a tangible military threat to the U.S. homeland. This distinction explains why Britain’s eventual disclosure of the telegram was interpreted as a deliberate attempt to force American intervention after other pressures had failed. The timing of the release, shortly before the United States entered the war, further reinforced this interpretation.

While this diplomatic explanation accounts for the impact of the Zimmermann Telegram, it does not fully explain the timing of Britain’s decision to withhold the information for several weeks. If Britain’s sole objective had been to provoke American entry into the war, immediate disclosure following interception in January 1917 would have been the most direct course of action. Instead, British intelligence delayed informing the United States until late February. This delay suggests that additional constraints shaped British decision-making. Specifically, Britain faced significant risks in revealing how the telegram had been obtained, risks that outweighed the potential diplomatic benefits of immediate disclosure. These constraints point to a deeper motivation rooted in intelligence security rather than diplomacy alone.

At the time of interception, British intelligence had obtained the Zimmermann Telegram by monitoring American-owned transatlantic cables. Germany used these cables to transmit encrypted diplomatic messages with U.S. permission, assuming they were secure from enemy surveillance. British access to these communications represented a significant intelligence advantage, but also a serious diplomatic liability. If American officials learned that Britain had intercepted messages sent through their own communication networks, it would have constituted a violation of American neutrality and sovereignty. Such a revelation could have severely damaged Anglo-American relations and jeopardized any possibility of future alliance. As a result, Britain could not safely disclose the telegram without addressing the problem of its source.

British intelligence officials faced a dilemma: revealing the telegram immediately would have raised unavoidable questions about how it had been intercepted. Without a credible alternative explanation, disclosure would have exposed Britain’s surveillance of American communication channels. Attempting to fabricate a false source at this stage would have risked undermining the telegram’s authenticity, as American officials would likely demand verification. Moreover, premature disclosure could have alerted Germany to the vulnerability of its diplomatic communications, prompting changes that would have neutralized British intelligence capabilities. The decision to delay was therefore not a matter of diplomatic calculation alone, but a necessary measure to protect intelligence sources and methods.

To resolve this problem, British intelligence delayed disclosure until it could present the telegram through a communication route that did not involve American networks. By obtaining a version of the telegram sent from the German ambassador in Washington to Mexico City, Britain secured an alternative source that could plausibly explain how the information had been acquired. This allowed British officials to share the contents of the telegram while concealing their interception of American cables. The delay thus served a practical intelligence purpose: it ensured that the United States could be informed without exposing the methods used to gather the information.

The existence of an alternative source also allowed the United States to verify the authenticity of the telegram. Without such verification, American officials might have questioned whether the message was genuine or whether it had been manipulated for political purposes. Providing a version of the telegram obtained through a diplomatic channel unrelated to American networks reduced skepticism and strengthened the credibility of the disclosure. At the same time, British officials consistently denied accessing American communication channels, reinforcing their commitment to protecting intelligence secrecy. These denials were not attempts to obscure the telegram’s significance, but deliberate efforts to prevent the exposure of British surveillance capabilities. The timing of the telegram’s release in late February 1917 coincided with rising tensions following Germany’s renewed unrestricted submarine warfare, which amplified its political impact. British officials waited until they could disclose the telegram without compromising intelligence operations or provoking diplomatic backlash. This careful timing demonstrates that the protection of intelligence capabilities governed Britain’s actions more than the immediate desire to influence American policy.

Britain withheld information about the decoded Zimmermann Telegram until late February 1917 for two interconnected reasons. While the eventual disclosure did contribute to American entry into the war, the delay itself was primarily driven by the need to protect British intelligence capabilities. Revealing the telegram too early would have exposed Britain’s interception of German communications transmitted through American networks, risking diplomatic fallout and the loss of valuable intelligence advantages. By waiting until an alternative source could be presented, Britain ensured both the credibility of the information and the secrecy of its intelligence operations. This episode demonstrates that intelligence security, rather than diplomacy alone, played a decisive role in shaping Britain’s decision to delay disclosure.

Ankur Phadke is a third-year International Relations and Public Policy student. He has served as Webmaster of the Attaché Journal of International Affairs since 2024.

References

1. Boghardt, Thomas. 2012. The Zimmermann Telegram : Intelligence, Diplomacy, and America’s Entry into World War I. Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 2012.

2. Freeman, Peter. 2006. “The Zimmermann Telegram Revisited: A Reconciliation of the Primary Sources.” Cryptologia 30 (2): 98–150. doi:10.1080/01611190500428634.

3. Ferris, John. 2021. “Behind the Enigma: The Authorized History of GCHQ, Britain’s Secret Cyber-Intelligence Agency.” doi:10.21810/JICW.V3I3.2795.

4. National WWI Museum and Memorial. 2024. “Zimmermann Telegram.” National WWI Museum and Memorial. 2024. https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/zimmermann-telegram.

5. Tuchman, Barbara W. 1966. The Zimmermann Telegram. Macmillan.