Amelia Dease | Originally Published: 13 December 2025

Artwork by Amelia Dease

Russia excuses torture, but draws the line at kids cage-fighting. In 2016, Chechen strongman Ramzan Kadyrov was scolded by the Russian Ministry of Sport for hosting MMA matches where children under 12, including Kadyrov’s own, participated in televised bouts. Kadyrov’s patronage of the sport is memorialized in the form of his state-of-the-art MMA gym in Grozny. Named for his late father Akhmat Kadyrov, “Fight Club Akhmat” (FCA) has hosted numerous UFC stars such as Magomed Ankalaev, who lost his belt this past October, and Khamzat Chimaev, the current middleweight title-holder as of this past summer.

At the time of writing, 12% of ranked male UFC fighters hail from the Caucasus. Compared to the small number of people in the world belonging to Caucasian ethnic groups, their disproportionate representation in the UFC is striking. Why are the Caucasus so well-represented in the upper-echelons of MMA? I argue that the dissolution of the USSR and subsequent squashing of independence movements in Russia’s ethnic republics has created the perfect conditions for a militarized masculinity to emerge in these regions.

We needn’t look any further than Dagestan’s Khabib Nurmagomedov, who put the Caucasus on the UFC map with his masterful defeat of Connor McGregor in 2018, for an example. Nurmagomedov’s father, Abdulmanap, served in the USSR military for two years, as mandated by conscription policies at the time. It was in the military where he perfected his judo. Following his discharge, he went to Ukraine to learn combat sambo. Since then, he has coached young Dagestani men in these techniques, producing two UFC champions in Islam Makhachev and his own son Khabib. The success of Abdulmanap’s disciples can be attributed to his old-fashioned, no-bullshit coaching style: a now-viral home video of Abdulmanap’s shows a 9-year-old Khabib wrestling a bear in Dagestan’s foothills as his father corrects his technique. Another video shows a reporter asking a young Khabib if he has a girlfriend. Khabib blushes, and his father steps in to answer the question, assuring the reporter that Khabib is married, belongs to his wife, yet doesn’t see her when he has a fight scheduled.

Compared to Khabib Nurmagomedov, the ethnic republics of the North Caucasus have fared comparatively poorly in their respective battles with Russian bears. Despite a brief period of de-facto independence, Chechnya has failed to permanently come out from under the yoke of the Russian Federation. The neighbouring republics, Ingushetia and Dagestan, achieved even less autonomy. Russia seeks to keep these regions plagued with instability and economic desolation.

Beginning in the 19th century, Chechens resisted Russian southward imperialism into their territory. With belief in Islam, a warrior tradition, and distinct social structures in the form of teips, Chechens considered themselves different from ethnic Russians and took pride in their history and culture. Following the fall of the Tsar, the Chechens enjoyed a brief period of independence until the region was brought back into the Russian fold under the name of the “Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.” In the USSR, ethnic Chechens were locked out of political power structures, as they could not be First Regional Secretaries in the Communist Party of the Republic. The power vacuum created by the dissolution of the USSR was leveraged by various historically distinct peoples of the Soviet Union, including the Chechens. Chechens were all-too-familiar with Russian oppression, given the expansionist policies of the tsardom. Yet, the political opportunity that Chechens were presented with in 1991 required them to deploy different tactics of resistance than were used in historical conflicts. Alongside Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, Chechnya’s Dzhokhar Dudayev declared independence from the Soviet Union. The fight for the modern independence of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria remains a decisive example of urban warfare.

During the first Chechen war, Chechen men called on their warrior history and put up a formidable defence of their nation. Heavy losses on the Russian side, coupled with the indiscriminate and inhumane bombings of Chechen non-combatants made the war unpopular in Russia, resulting in the withdrawal of troops from the region. The interwar period left in its wake a factionalized standing army of Chechen insurgents and a devastated capital city.

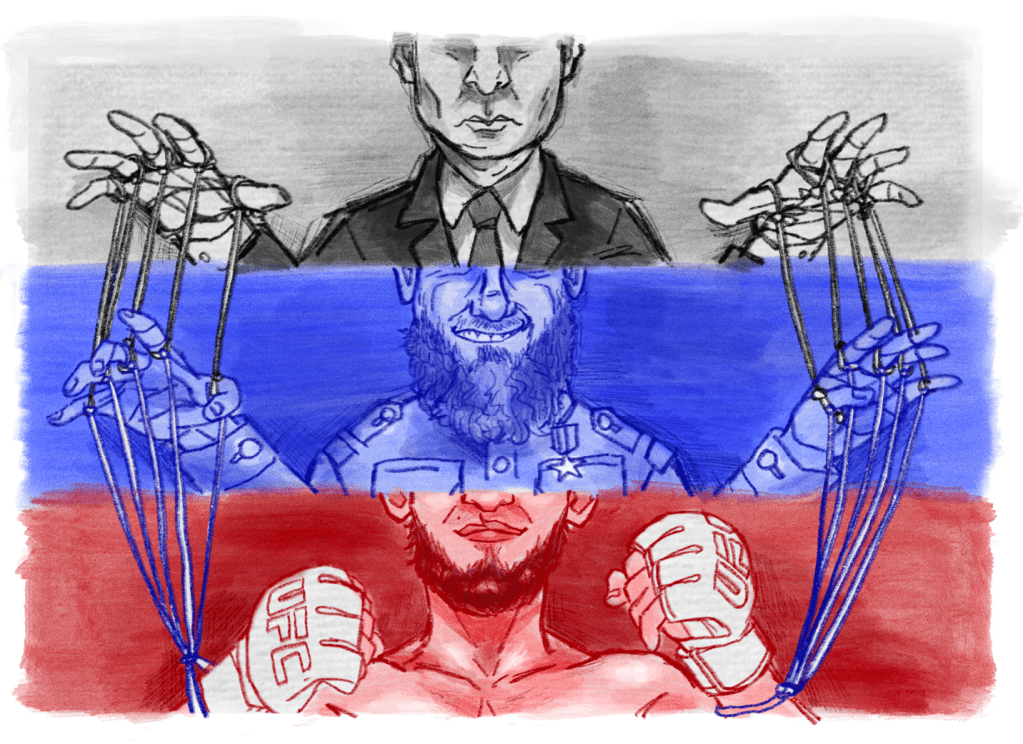

The perceived chaos in Chechnya gave young Prime Minister Vladimir Putin an opportunity to prove that he was made of stronger stuff than the aging Boris Yeltsin. After a decisive Russian victory, Putin installed local Mufti, Akhmat Kadyrov, as president of the Republic. In exchange for promising to eliminate the remaining insurgents hiding in the mountains, Putin afforded Akhmat a degree of autonomy unheard of in the Russian Federation. Akhmat was succeeded by his son Ramzan, who arguably enjoys an even more enhanced licence to kill than his father.

Putin has come under fire for allowing Kadyrov to repeatedly violate the Constitution of the Russian Federation. Thus far, there is no indication that Putin seeks to reign in Kadyrov. In fact, the instability facilitated by the Kadyrov dynasty is a feather in Putin’s ushanka. The Federation allegedly offers the Kadyrov government €14,000 for each “terrorist” that is eliminated. These funds are meant to be distributed to Kadyrov’s personal security forces, aptly named the Kadyrovites, as compensation for cleansing the Republic of evil.

The Kadyrovites fought on the insurgent side under Ahkmat Kadyrov in the first Russo-Chechen war, and then followed Ahkmat to Russia’s side for the second. Following Ahkmat’s death, the Kadyrovites passed to his son’s control. Young men with limited postwar economic opportunities joined the Kadyrovites, who train at the aforementioned Fight Club Akhmat under the guise of practicing MMA. Ramzan’s son, who he bills as his successor amid health concerns, has trained under FCA’s Khamzat Chimaev.

The monetary rewards offered to the Kadyrovites for each “terrorist” they drop on the gold-gilded doorstep of Kadyrov facilitate the capture of innocent Chechen civilians. The most horrifying account of this is found in the Republic’s practice of hunting queer Chechens, who are seen as an affront to Kadyrov’s personal brand of Islam.

Thus far, the Russian Federation has not agreed to prosecute the Kadyrovites for any of their gross human rights violations. There has been not a peep from Putin on the matter, which further illustrates that instability in the region works in his favour. For Putin, the atrocities perpetuated by Kadyrov are a small price to pay for the assured subordination of the region.

References

1. Associated Press. “Kremlin Calls for Investigation into Televised Fights between Kids as Young as 8.” Toronto Star, October 6, 2016. https://www.thestar.com/news/world/kremlin-calls-for-investigation-into-televised-fights-between-kids-as-young-as-8/article_ab58ea54-c2ae-5302-9bf6-add8646efb52.html.

2. BBC Monitoring Former Soviet Union. “Russian Paper Says Chechen Security Service Fuels Instability in North Caucasus.” BBC, January 18, 2005.

3. Blauvelt, Timothy K. “The Caucasus in the Russian Empire.” In Routledge Handbook of the Caucasus, edited by Galina M. Yemelianova and Laurence Broers. Routledge, 2020.

4. ESPN MMA. “Khabib Compares Fighting to Coaching + Talks Preparing for #UFC311 & Remembers His Dad | ESPN MMA.” YouTube, January 13, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tWDYmXh-lvA.

5. France, David. “Welcome to Chechnya.” HBO Films, January 26, 2020.

6. Gel’man, Vladimir. Authoritarian Russia: Analyzing Post-Soviet Regime Changes. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015.

7. Gilligan, Emma. Terror in Chechnya: Russia and the Tragedy of Civilians in War. Princeton University Press, 2014.

8. Huérou, Anne Le, Aude Merlin, Elisabeth Sieca-Kozlowski, and Amandine Regamey, eds. Chechnya at War and Beyond. 1st Edition. London: Routledge, 2014.

9. Loizeau, Manon. Chechnya: War without Trace. Edited by Bruno Joucla and Mathieu Goasguan. Internet Archive, 2015. https://archive.org/details/WarWithoutTrace.

10. Luchterhandt, Otto. “The Chechen Attempt at National Independence and the Internal Reasons for Its Failure.” Yearbook on the Organization for Security Policy at the University of Hamburg, 2000, 179–201. https://www.ifsh.de/file-CORE/documents/yearbook/english/00/Luchterhandt.pdf.

11. Merlin, Aude. “The Postwar Period in Chechnya: When Spoilers Jeopardize the Emerging Chechen State (1996–1999).” In War Veterans in Post War Situations: Chechnya, Serbia, Turkey, Peru, and Côte D’Ivoire, 219–39. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

12. Sadam Astamirov. “Khabib Nurmagomedov vs. Bear.” YouTube, April 10, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mjfOeLQG9-M.

13. Sokirianskaia, Ekaterina. Bonds of Blood?: State-Building and Clanship in Chechnya and Ingushetia. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023.

14. Scicchitano, Dominic. 2021. “The ‘Real’ Chechen Man: Conceptions of Religion, Nature, and Gender and the Persecution of Sexual Minorities in Postwar Chechnya.” Journal of Homosexuality 68 (9): 1545–62. doi:10.1080/00918369.2019.1701336.

15. thelastwitcher87. “Khabib’s Dad Roasting Him (Old Video).” Reddit.com, 2025. https://www.reddit.com/r/ufc/comments/1mxrglf/khabibs_dad_roasting_him_old_video/.

16. The Telegraph Foreign Staff. “Ramzan Kadyrov Accused of Child Cruelty after Entering Pre-Teen Sons in Televised Cage Fights.” The Telegraph, October 6, 2016. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/10/06/ramzan-kadyrov-accused-of-child-cruelty-after-entering-pre-teen/.

17. UFC. “Athlete Rankings.” Ufc.com, November 25, 2025. https://www.ufc.com/rankings.

18. Yemelianova, Galina M., and Laurence Broers, eds. Routledge Handbook of the Caucasus. Routledge, 2020.